Mauro Porcini has spent much of his trailblazing career at the top of some of the world’s biggest companies. Therefore, it’s easy to wonder: How the heck does one actually become a “Chief Design Officer”? Well, when you talk to Porcini, you immediately understand why.

Mauro Porcini has spent much of his trailblazing career at the top of some of the world’s biggest companies. Therefore, it’s easy to wonder: How the heck does one actually become a “Chief Design Officer”? Well, when you talk to Porcini, you immediately understand why.

A driven, determined evangelist for the power of design, no one elucidates the craft and its potential quite like him. Suddenly, “Chief Design Officer” doesn’t seem all that curious in corporate architecture. It just makes perfect sense.

Originally from Northern Italy, Porcini began his career as a product designer before launching Wisemad SrL with producer and artist Claudio Cecchetto. He then spent a decade at 3M, revolutionizing the company from within as CDO, before taking the title with him to PepsiCo, where he also serves as SVP today.

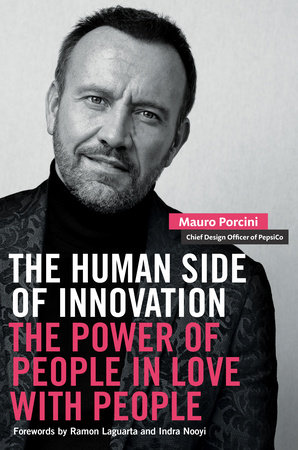

With decades of hard-won wisdom under his belt, he is set to share some of his best lessons in his forthcoming book The Human Side of Innovation: The Power of People in Love With People—and at the HOW Design Creative Leadership Summit, Oct. 11-12.

In our exclusive Q&A, Porcini riffs on his roots, how designers can forge a path to the C-suite, and the future of the profession at large.

Mauro Pornici, thank you for chatting with us. How did your creativity manifest at an early age?

I was inspired by my parents. My father is an architect, but he was always obsessed with art and he would draw all day, all the time. Today he’s in his 80s and he draws and paints every day. My mom was working in finance, but she hated it, and she left work when she was 38. Her dream was to be close to her kids and see them growing, and she was in love with writing. She would write poems and thoughts every day. And so here I am, inspired by these two parents in the broader field of humanism.

In the beginning, I was emulating, imitating. My father would use a technique called pyrography—you have a heated poker, and you burn images into wood. And so I was doing the same with little pieces of wood and scraps when I was 6 or 7, trying not to burn myself. One day I decided to change the substrate, the material. Instead of using wood, I decided to use leather. And eventually after scraps of leather, I started to do it on wallets and belts. I still have a belt that I created back then.

Essentially, I moved from creating art, what my father was doing, to creating objects. My first memory of going from emulation to innovation was when I changed the material—all of a sudden, I did something that was my own.

You had a pretty legendary run at 3M. What first drew you to the company?

I invested in the world of digital early on in the early 2000s, creating a company with this big Italian celebrity, Claudio Cecchetto. We lasted two-and-a-half years, and then the internet bubble burst. There was no money, no way to make money, especially for a self-funded company like ours. Long story short, we’re closing the company, and then in parallel, 3M is searching for somebody to start infusing a little bit of design in the periphery of the American empire.

I always define it in this way because imagine this big American corporation based in Minnesota; Italy was a little country for them, a little business, but there was a visionary leader at 3M Italy. And the visionary leader of 3M Italy proposed hiring a young designer in Italy to start this capability. They offered the job to somebody much more senior than me, but he had just opened his own design firm and he declined, and it was offered to me.

The company took a leap of faith, and they were also probably like, you know what? It’s a safer bet. If it doesn’t go well, the guy’s just 27, [he’ll be fine]. I started with this dream of infused human centricity. It was a very naïve dream. I was going to be the coordinator of design in one of the six businesses of the company in the European region. How could I change design and innovation at this kind of company?

So the dream obviously was naïve, but I always say—and this is one of the pages in my book—if you don’t have a dream, you will never be able to make it come true. You need to dream, think big, dream, and then act—and things happen.

Know that when you have a dream, people will think you’re crazy. Society will try to normalize you. We dream when we are children; when we’re kids, we are dreamers by definition. And then sooner or later, you start this process where you are surrounded by people who tell you that dreaming is a childish kind of thing, it’s not OK. But why? Because society once again wants to normalize people. They don’t want too many people to dream and go in different directions. They need to control people.

So too many dreamers is a problem. We forget how to dream—but we should always dream. And when we dream, we should always be aware that we will face all kinds of roadblocks and people pushing back. So that was the naive dream of a kid at 3M. And then 10 years later, I became the chief design officer of the company.

You’ve become iconic for elevating design internally at different companies, be it 3M, Pepsi—what’s the key to showing all the incredible potential and power of design to the rest of the C-suite?

As I told you earlier, I had this passion for writing. And I think it’s not just the act of writing, but the root cause of the passion is sharing and storytelling and communicating. I also have a kind of mentorship drive inside myself—I need to give back, to both share the knowledge that I may have and also the love that I have. I started writing and speaking at conferences very, very early on, even before 3M.

So early on I started to define with incrementally more and more clarity over the years, “what is the role of design? What is its impact, what is working, what is not?” If anybody asks me what you need to do to build a design culture—or any kind of culture—in an organization, [I say that] you need to be clear about what it is, what its impact is, how you can grow it. And so in my case I decoded that by speaking at conferences and writing articles and giving interviews because it forced me to do so.

The second thing is that actual projects trump any kind of storytelling. You can storytell to death, but if you don’t have proof points, nobody will believe you. So the storytelling is important to get your foot in the door to get some initial funding, to get the investor or the sponsor to believe in you. But then, as soon as possible, you need to land some proof points.

Eventually I started to find what they call the co-conspirators inside the company—people that would understand the value of a designer; they could take a leap of faith and try a different kind of project or a different approach to something with this kid that was proposing it. With co-conspirators, I started to build the proof points, the projects that went in the right direction.

Once you start to have a few projects, you will have more people that will come to you. You start to have more proof points and more proof points, until you build a critical mass that really shows the company that you’re bringing value to the organization.

You break down the overall process of infusing innovative design into the corporate ecosystem into five phases.

The first one is denial—when the company doesn’t understand that you need a different approach, a different culture. If the company stays in denial, the company probably will disappear—think about Kodak or Blockbuster, when you are in denial about, for instance, a new technology disrupting your industry. In most cases, companies have CEOs and business leaders who realize that they need change.

And so after denial, you move to the second phase, when you find, for instance, a design leader to hire and try to change the mindset of an organization, the cultural organization. In this phase, it’s very important to understand that when you bring in this person, most of the company will push back. They will react in a negative way and try to protect the status quo.

I call the second phase the hidden rejection, meaning that you won’t realize it right away because people will pretend they’re OK with you. For a variety of different reasons, they won’t tell you to your face, “I don’t care about you and design.” But eventually they will show a passive aggressive kind of behavior that will stop the new culture from progressing.

It’s important to realize that because essentially what you need to do when you are broadening the company to change the culture is to find the co-conspirators I was talking about. Through them, you move to the third phase, the occasional leap of faith. This is when your co-conspirators are willing to take a leap of faith and try something new and build the proof points. When you scale the proof points, the company realizes that this thing works.

You then move to the fourth phase, what I call the quest for confidence—essentially, when the people in the organization are like, “Yeah, there is a lot of value here,” but then there is the day-to-day, and this time it’s not one project here and there. This time it’s hundreds of projects, a scale with hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions of dollars, at stake. And so this is when you need to build confidence in the organization with the right processes and tools and ways of working so that this works at scale.

If you succeed, then you move to the fifth phase—what I call holistic awareness, when the company finally gets it, and everybody works together to support the new culture.

In your new book, you detail how innovation is an act of love. Tell me a little bit more about that.

First, let’s define what an act of love is. It’s something that you do as a person, for another person that you deeply care about, that you really love. So imagine your kids, your parents, your significant others, and your friends. What do you do if you love them? You try to surprise them. You try to understand what they need and what they desire and what they dream. And you try to fulfill all of that. This is what an act of love is.

First, let’s define what an act of love is. It’s something that you do as a person, for another person that you deeply care about, that you really love. So imagine your kids, your parents, your significant others, and your friends. What do you do if you love them? You try to surprise them. You try to understand what they need and what they desire and what they dream. And you try to fulfill all of that. This is what an act of love is.

And now pause that thinking for a moment and think about the design world and the very first acts of design that ever happened in the history of humanity—when historic man started to take something that was available in nature and started to modify it for a specific need.

They started to manipulate stones to build hunting tools, or tools to prepare food. Later on, tools to decorate their body. So tools to fulfill a series of needs that Maslow centuries later defined in his pyramid. It was about safety, it was about nurturement and all the physiological needs—and then it was self-expression, it was about yourself. It was even about transcendence when they started to build objects for the gods.

So from the very beginning, design was all about creating objects to fulfill specific needs and wants for yourself and for others. For years and for centuries, we created our own products as an act of love for the people surrounding us, until … we started to delegate the creation of these products to other people for us, hoping that those people would protect the love.

The problem is that over the thousands of years we started to build companies and organizations and brands, still to amplify that original act of love, to produce more and more of those products that were all about creating something that we needed and wanted.

The problem is that with scale came a new focus from attention to people, to attention to profit. We moved literally from the human interest to the economic interest. We lost the original meaning of innovation as an act of love, or design as an act of love. And it’s really important to take it back, not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because it’s the ethical thing to do. It’s what we need.

Now, anybody can come up with an idea, get funding, and go straight to the end user through the commerce platform and communicate to them through social media. In this kind of world, either you create extraordinary products for the people you serve as a company, or somebody else will do it on your behalf.

So the big companies, for the first time in history, need to produce excellence. They need to deeply understand people and create extraordinary products for them. They need to put this act of love for people—“People in Love With People,” the subtitle of my book—at the center of everything they do.

Do you have a personal design philosophy? Or any sort of design ethos that drives you?

What drives me is for sure this idea of creating value for people. As designers, by definition we are thinkers and doers and we touch the life of people every day. If we do it in the right way—if we’re driven by purpose, if we’re driven by the idea of creating positive value in the life of people—we can really create a better world, and ultimately we can drive happiness.

If we are instead driven by other factors—making money for our company, and that’s it, or we don’t really care about creating positive value for society—we can be [a negative force] for this world and for this planet. We can create products that society doesn’t need and are not necessary. So I think we need to be driven by this mission.

We also need to acknowledge that we don’t live in a perfect world, and so what we need to do is to be driven by this positive intent, be driven by purpose, and then we will work within the ecosystem we live in, with the companies and the brands to change everything and evolve everything from within. It’s super easy to stay out[side companies] and blame the world. It’s so insanely difficult to try to change things at scale from within.

If you are driven by purpose, if you want to build a better world, either build your own startup and let’s hope that becomes the next multi-billion dollar company, or join companies that give you platforms to evolve the system.

What do you feel is the future of design?

I think we should divide two aspects of design. One is design as the discipline—the skill of designing products or brands or services, experiences physical or digital. So, the definition that is really focused on the output. The second is the designer’s way of thinking. I try to define it in the book.

I do think that the way of thinking typical of our community will become more and more ingrained in the DNA of companies because for financial reasons they need to become more human-centered. And so the kind of approach typical of the designer, a creator with a humanistic focus, will be more and more the kind of thinking that defines the culture of the companies out there, more than in the past.

Designers therefore will start to play more and more relevant roles in organizations big and small. What I don’t know is if we’ll be able as a community to somehow own this idea of human centricity, to become ambassadors of this. And I say I don’t know because sometimes we’re not aware of it. We don’t understand that this is a phenomenal asset that we bring to the table.

I pitch this idea of design as a synonym of human-centered innovation. This is what I tell these companies: “Look, this is what designers do, this is how they’re trained at school, this is what they were taught.”

We’re taught to innovate in three dimensions, desirability, feasibility and viability. The word of business, of human beings, and technology. This is what your company calls innovation—but we are trained in this, we are the only community trained in it. Marketing is not trained on the feasibility part of this, on the technology part of it. If you study science, if you study engineering, you are not trained in the human side of it. We are trained in these three dimensions. So if you embrace design thinking, you are embracing human-centered innovation.

The problem is that we need to first of all be aware as designers that this is what we do, and start translating what we do in a language that is understandable by the business world, or else they will not be able to leverage us.

Second, we need to make sure that we don’t get out of school and forget everything we learned just because we get trapped in a very narrow definition. We need to make sure that either we go to companies that can empower us to be really who we are supposed to be, what we learn in school.

At 3M or at PepsiCo, I came in and they told them, look, I’m going to give you everything you need from me. I’m going to give you graphic design and industrial design, digital design—I’ll give you that so you’re going to be happy. But then I started to push like crazy a different definition of design in parallel, and I showed them by doing stuff—the proof points I was talking about earlier. The more you show that value, the more they recognize that design can actually play that kind of role.

So I really hope that through platforms like HOW—the communication platform, the conferences, everything you do—and then other platforms that are out there, both in design and business, as well, we spread this message. Design is human-centered innovation.

Business world: Understand it and leverage design. Design world: Understand it and position yourself in this way.

Get More of Mauro Pornici

For more from Mauro Porcini, check out his book, The Human Side of Innovation: The Power of People in Love With People. Also, don’t miss him at the HOW Design Creative Leadership Summit, Oct. 11-12. Finally, follow him everywhere on social media: Twitter, Instagram or LinkedIn.